self-historisation

the term

Self-historicisation, as defined by curator Zdenka Badovinac, refers to an informal system of historicisation practised by artists who, due to the absence or dismissive attitude of official institutions, are forced to become the architects of their own historical context. It is a practice born of necessity, most notably in regions like Eastern Europe during the socialist period, where neo-avant-garde art was systematically ignored. In this void, artists take on the roles of archivist, historian, and narrator, gathering documents related to their own work, their peers, and the broader conditions of artistic production. Crucially, self-historicisation is not about creating an «objective» history from an external position; it is an inherently personal and involved act of preservation that highlights the individual’s role in constructing any narrative, which always involves exclusion. It advocates for «universal archives» — heterogeneous, unsystematic, and incomplete — as an alternative to hegemonic «universal collections» based on power and ownership.

the relevance

The relevance of self-historicisation is acute in today’s globalised art system. While major Western institutions claim to present a «global» art history, Badovinac argues they often merely incorporate non-Western art into pre-existing frameworks, reinforcing a singular viewpoint while strengthening their own influence. Self-historicisation acts as a vital counter-force to this homogenisation. It insists on a multiplicity of transparent, situated narratives that expose the processes of their own creation. In the digital age, where personal documentation is ubiquitous but often subject to algorithmic control and corporate platforms, the principles of self-historicisation — personal agency, narrative sovereignty, and the preservation of marginalized contexts — resonate beyond galleries. It becomes a model for challenging dominant historical algorithms, whether in art, social media, or public memory, advocating for a polyphony of voices in an increasingly standardized world.

examples of self-historicisation

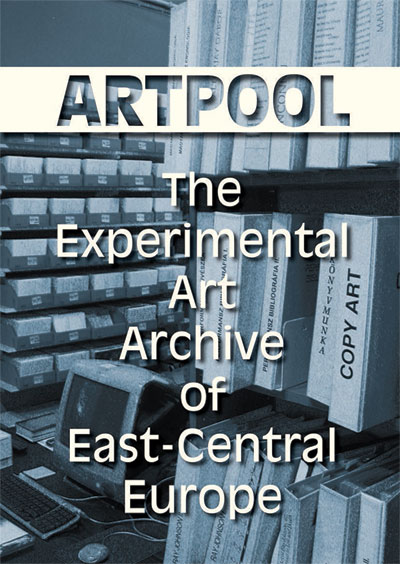

Artpool (György Galántai and Júlia Klaniczay, Hungary)

Founded in 1979, Artpool is a paradigm of self-historicisation. Operating unofficially under socialism, it became a central archive and network for mail art, experimental music, and performance that the state ignored. By systematically collecting correspondence, artworks, and publications, Artpool created a living, alternative art history that provided the essential context for a generation of artists, later becoming an invaluable public resource.

Lia Perjovschi and the Contemporary Art Archive (CAA), Romania

Lia Perjovschi Knowledge Museum

Lia Perjovschi Knowledge Museum

Emerging from the cultural isolation of the Ceaușescu era, Perjovschi’s life’s work is a «knowledge museum.» Her CAA, comprising hand-drawn timelines, scrapbooks, and collected objects, represents a desperate and dedicated act of self-education and reconnection with global art discourse. It is a physical archive of a personal quest to overcome informational blackout, embodying the trauma and resilience Badovinac describes.

Lia Perjovschi Knowledge Museum

IRWIN (Slovenia)

Irwin works and projects

The NSK collective engages in meta-critical self-historicisation. Their Was ist Kunst? series (1984-1996) functioned as a visual archive of conflicting iconographies, from which they distilled their own personal «icons.» Their East Art Map project (2002-2005) took this further, attempting a collective mapping of Eastern European art. The project’s deliberately «unsystematic» and incomplete result was its most significant finding: proving the impossibility of a single, cohesive narrative for the region and highlighting the subjective nature of all historical construction.

Irwin works and projects

The Atlas Group / Walid Raad (Lebanon)

The Atlas Group

Expanding the concept beyond Eastern Europe, Raad’s fictional archive on the Lebanese Civil Wars uses self-historicisation to probe the limits of historical truth. By inventing archives, photographers, and documents, he does not merely fill a gap but questions how trauma is processed, documented, and believed. His work asserts that in contexts of extreme fragmentation, the artistic, subjective act of archiving becomes the most authentic form of testimony.

The Atlas Group

The Atlas Group

Zofia Kulik (Poland)

Activities with Dobromierz

Kulik’s meticulous photographic documentation of Polish artistic life under socialism, first in the collective KwieKulik and later in her own practice, constitutes a powerful archival act. She preserved the ephemeral performances and everyday realities of the unofficial art scene. In her later photomontages, she repurposes these and other archival images to deconstruct iconographies of power, demonstrating how the self-historising archive can become raw material for critical artistic practice.

Activities with Dobromierz

conclusion

In conclusion, self-historicisation is far more than a compensatory tactic for missing archives; it is a critical methodology and a political stance. As defined by Badovinac, it challenges the authority of centralized, institutional art history by foregrounding the personal, the fragmentary, and the consciously constructed. The practice, as seen in the work of Artpool, Perjovschi, IRWIN, Raad, and Kulik, creates not definitive histories but open-ended «apparatuses of remembering» that are deeply intertwined with personal experience and collective trauma. In the contemporary world, where globalization often masks persistent power imbalances, self-historicisation remains an essential tool for asserting agency, preserving difference, and insisting that true global understanding emerges only from a chorus of individual voices, not from a single, hegemonic narrative. It ensures that history is a lived and contested process, not a finished product owned by the powerful.

GLOSSARY OF COMMON KNOWLEDGE