The Evolution of Environmental Art Movements

Before the world whispered sustainability, artists were already shouting.

This chapter takes a journey through time, from the days of the Avant-garde, tracing the roots of environmental art from the raw defiance of the 1960s land artists to the intricate assemblages of today’s ecology-conscious creators. It explores how visionaries like Robert Rauschenberg and Agnes Denes defied the pristine canvas, pulling art from the very earth itself. Each movement, from the protest-driven Earthworks to the refined aesthetics of contemporary Eco-Art, has deepened art’s role in environmental discourse. As the climate crisis intensifies, we must ask: has art been leading the fight all along, and have we just begun to listen?

Origins in the 1960s and 1970s

The ecological art movement, also known as environmental art, has evolved over several decades, responding to growing concerns about environmental issues.

The origins of ecological art is rooted in the Industrial Revolution, a period marked by rapid industrialization and urban growth. As factories proliferated and coal-powered machines became widespread, the atmosphere grew increasingly polluted with smoke and soot. This environmental degradation sparked not only public health concerns but also early artistic and philosophical responses to humanity’s growing disconnection from nature. Artists, writers, and thinkers began to react to the visible consequences of industrial progress, planting the seeds for what would later evolve into the ecological art movement. Over time, these initial reactions matured into a broader artistic practice that seeks to raise awareness about environmental issues, foster sustainability, and reconnect people with the natural world through creative expression.

The roots of ecological art can be traced back to the 1960s and 1970s, when artists began to question the relationship between humans and nature. This period saw the rise of environmental activism, and artists became increasingly concerned about environmental degradation and its impact on ecosystems.

Land Art: Artists like Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer, and Nancy Holt were pivotal in shaping the early ecological art movement with their land art. They created large-scale outdoor installations using natural materials, often with an emphasis on the impermanence of human interventions in the natural world. Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970) is a key example, demonstrating how art could engage directly with the landscape while also reflecting environmental themes.

Earth Art: Similar to Land Art, Earth Art focused on natural elements, like soil, rocks, and plants. Artists like Andy Goldsworthy used natural materials to create temporary works that emphasized the cycle of life and decay in nature.

Detail of Robert Smithson, «Spiral Jetty,» 1970. Long-term installation in Rozel Point, Box Elder County, Utah. Photo: Eppich/Esmay/Tang, J. Paul Getty Trust. Collection Dia Art Foundation.

Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty is one of the most iconic and influential works in the history of ecological and land art. Created in 1970 on the northeastern shore of the Great Salt Lake in Utah, the artwork is a massive spiral-shaped jetty made of mud, salt crystals, basalt rocks, and water. It stretches approximately 1,500 feet into the lake and coils counterclockwise from the shore into the water.

Spiral Jetty reflects Smithson’s deep interest in entropy, geology, and the interaction between humans and the environment. Rather than placing art in a gallery, Smithson chose to work directly with the landscape, allowing natural processes like erosion, water levels, and salt accumulation to shape the work over time. This engagement with natural forces made Spiral Jetty a powerful symbol of the emerging ecological art movement, which emphasizes sustainability, the passage of time, and the interconnectedness of natural and human-made systems.

F_Michael-Heizer, -Rift-1, -1968 Jean-Dry-Lake, -Nevada.

Michael Heizer’s Rift is a significant work within the land art movement, reflecting the artist’s deep engagement with landscape, scale, and the raw power of natural forms. Heizer’s land-based works, including Rift, often involve physically altering the earth, cutting, removing, or displacing large volumes of soil and rock, to create minimal yet powerful interventions in the natural environment. These works invite viewers to contemplate the tension between nature and human impact, permanence and change, presence and absence.

In the context of ecological art, Rift and Heizer’s broader practice can be seen as a dialogue with the land that acknowledges both its grandeur and vulnerability. Though not explicitly ecological in the activist sense, Heizer’s work draws attention to the Earth’s scale and structure, prompting reflection on humanity’s relationship with the environment. By working directly with the terrain, Heizer challenges conventional art spaces and encourages a deeper, more embodied awareness of the physical world.

Sun Tunnels (Great Basin Dessert, Utah) (1973-76) by Nancy Holt

Nancy Holt, another pioneer in conceptual and public art, played a vital role in the evolution of ecological and land-based art. As a key figure in the Land Art movement that emerged in the late 1960s, Holt was part of a generation of artists who began to reject the confines of traditional galleries and instead created works directly in the landscape. This shift marked an important moment in the development of ecological art, as artists sought to engage more deeply with natural environments and challenge the separation between art, nature, and the viewer.

Holt is best known for Sun Tunnels (1976), a large-scale environmental sculpture located in the Utah desert. The work consists of four massive concrete tunnels, each 18 feet long and 9 feet in diameter, arranged in an open X-shaped formation. They are precisely aligned with the rising and setting sun during the summer and winter solstices, creating a direct connection between the artwork, celestial events, and the Earth’s cycles.

The 1980s and 1990s: Protest and Eco-Activist Art

During the 1980s and 1990s, ecological art began to integrate more directly with political and social concerns. Environmental issues became more urgent as artists turned their focus on waste, pollution, consumerism, deforestation, and the awareness about climate change grew. The art world moved from monumental earthworks to protest-driven eco-art. The rise of recycled art began, with artists turning discarded materials into thought-provoking installations.

Simultaneously, the rise of recycled art emerged as a powerful subgenre within ecological art. Artists started using discarded, found, and repurposed materials such as plastic waste, scrap metal, paper, and electronic debris to create installations and sculptures that were both visually compelling and environmentally conscious. By transforming trash into art, these creators not only critiqued the culture of overconsumption and waste but also demonstrated the potential for renewal and transformation. This shift represented a growing awareness within the art world that creativity could be a vehicle for ecological responsibility.

During this period, global environmental awareness grew—by 1992, over 1,700 scientists (including Nobel laureates) signed the World Scientists' Warning to Humanity, urging immediate environmental action.

Artists like Mierle Laderman Ukeles and Agnes Meyer-Brandis incorporated ecological themes into social and feminist contexts. Ukeles' Maintenance Art (1969–1980s) involved a series of performances and public projects that highlighted the often-overlooked work of maintenance, which is connected to both ecological and social sustainability.

Mierle Ukeles Laderman’s early Second Binding (1964), installed at the Queens Museum. Image: Ben Davis.

Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ early work Second Binding (1964) holds a significant place in the evolution of ecological and feminist art. Second Binding already demonstrated many of the conceptual seeds that would grow into her later ecological and maintenance-centered practice.

In Second Binding, Ukeles wrapped everyday objects in layers of clear plastic and tape, binding and preserving them in a ritualistic manner. This act of encasing and protecting can be interpreted as an early exploration of themes that became central to ecological art: preservation, containment, the relationship between human activity and material objects, and the tension between consumption and care. In the broader context of ecological art, this gesture can be seen as a commentary on the fragility of the environment and the need to recognize and preserve what is often taken for granted or deemed disposable. The plastic wrap itself, a material associated with waste and pollution, also serves as a subtle critique of the culture of excess and environmental neglect.

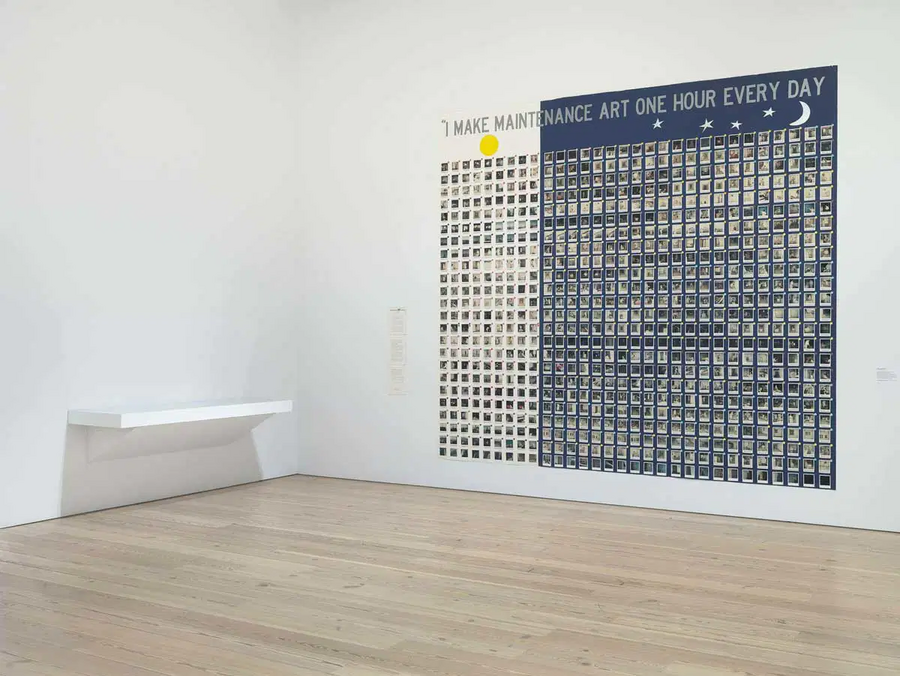

I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, 1976 via Whitey Museum of American Art

Washing/Tracks/Maintenance: Outside by Mierle Laderman Ukeles, 1973, via Brooklyn Museum

In her 1976 project I Make Maintenance Art One Hour Every Day, Mierle Laderman Ukeles collaborated with 300 maintenance workers over the course of two months at 55 Water Street, a massive skyscraper in New York City that once housed a branch of the Whitney Museum.

Ukeles had long wanted to focus on maintenance work within a skyscraper, recognizing that these towering structures depend on extensive human effort to remain operational. She worked alongside the staff during their eight-hour shifts, taking Polaroid photos and conducting interviews. Each worker was invited to consider one hour of their day as «art, ” and Ukeles asked them whether the photograph she took showed them doing work or making art. Their responses, paired with the images, were later exhibited, turning the mundane yet essential labor into something seen, valued, and dignified.

Ukeles redefined the notion of maintenance as a form of ecological care, extending beyond natural ecosystems to include built environments and the human systems that sustain them.

Contemporary Ecological Art (2000s to Present)

As the 21st century unfolded, climate change became impossible to ignore. Art became a direct tool for education, activism, and policy change. By 2023, nearly 77% of global citizens surveyed in a Pew Research study reported climate change as a major threat, reflecting how art has helped shape public perception.

Footage from The Weather Project (2003), installed in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern in London, captures the immersive experience of this monumental, site-specific work by artist Olafur Eliasson. The installation transformed the vast industrial space into a surreal, atmospheric environment that invited both awe and reflection. At its core was a massive semi-circular screen mounted on the far wall, positioned just below a ceiling made of large aluminium frames covered in mirror foil. This mirror ceiling visually doubled the space, creating the illusion of a full, glowing sun when the semi-circle was reflected above.

Approximately 200 mono-frequency lights were placed behind the screen, casting a deep, golden hue across the entire hall. Combined with a fine artificial mist pumped into the air, the space evoked the sensation of standing beneath an otherworldly sunset. Visitors lying on the floor or walking through the mist became part of the scene, their reflections merging with the architecture and other viewers in the mirrored ceiling above.

In the context of ecological art, The Weather Project resonates as a poetic commentary on the environment and humanity’s relationship with nature. By simulating a natural phenomenon within a controlled, artificial space, Eliasson prompted viewers to consider the fragility of real weather systems and the ways in which climate and atmosphere are increasingly shaped by human intervention. The work blurred the boundaries between art, science, and ecology, urging visitors to reflect on their place within larger environmental systems and the collective experience of the world around us.

Eco-activism and Public Engagement: Environmental artists today often collaborate with scientists, activists, and communities to address specific environmental issues. For example, artists like John Dahlsen and Aviva Rahmani work with communities to create works that not only engage the public but also take action toward environmental regeneration.

Sustainability in Materials: Contemporary ecological artists are increasingly concerned with the sustainability of the materials they use. Many artists are turning to eco-friendly practices, such as using biodegradable materials, and some are even developing new sustainable artistic techniques.

Conclusively for this chapter, in today’s world, art has the unique ability to stir emotions in ways that science and data alone cannot. A photograph of a melting glacier may inform us, but an installation that allows us to feel the melting ice in our hands makes it real. A documentary on deforestation may educate us, but an artwork built from the very remains of cut-down trees brings the grief of environmental destruction into our hearts.

Ecological art now intersects with various fields, including science, technology, and environmental policy. Digital media, interactive installations, and virtual reality are increasingly used to engage audiences with environmental issues in new and innovative ways. As audiences, we have a responsibility not just to admire, but to engage. To allow art to transform us. To take its messages beyond galleries and museums and into the decisions we make every day.

The question remains: will we finally hear what the artists have been saying all along?

Beardsley, J. (2006). Earthworks and Beyond: Contemporary Art in the Landscape. Abbeville Press.

Heartney, E. (2013). Art & Today. Phaidon Press.

Jordan, C. (2009). Midway: Message from the Gyre. Photography Series.

Muniz, V. (2010). Waste Land. Documentary Film.

Smithson, R. (1970). Spiral Jetty. Utah: Dia Art Foundation.

Taylor, J. (2011). The Silent Evolution. Museo Subacuático de Arte, Mexico.

Chin, M. (1991). Revival Field. Ongoing ecological art project.

Pew Research Center. (2023). Global Climate Change Survey.