The Role of Recycled Materials in Artistic Expression

What if Art isn’t newly created—but discovered, reimagined, and reborn?

Waste is no longer waste in the hands of the artist, it is a language, a material, a second life waiting to be unveiled. This chapter delves into the transformative process of taking the discarded and making it desirable. How does a rusted metal sheet become a sculpture of resilience? How does a pile of plastic bottles morph into a landscape of protest? Through the lens of recycled art, this chapter uncovers how artists challenge society’s perception of what is valuable, what is waste, and what stories lie between the two.

In a world increasingly defined by its consumption habits and environmental consequences, the artist’s role has never been more critical. One of the most profound evolutions in contemporary creative practice is the shift from pristine materials to those once deemed useless, scraps, waste, discarded objects.

Recycled materials have emerged not only as tools of artistic expression but as statements of resistance, sustainability, and social critique. This chapter explores how artists around the world are transforming the remnants of modern life into poignant, provocative works that challenge our understanding of value, beauty, and ecological responsibility.

Recycled art subverts traditional notions of aesthetics. What was once trash becomes treasure, not because it mimics the formality of «high art,» but because it conveys layered messages.

When an artist chooses to sculpt with scrap metal, paint on cardboard, or assemble installations from plastic waste, they are making a statement: about excess, about renewal, about the interconnectedness between culture and ecology. This shift mirrors a broader movement toward sustainability and circularity, positioning the artist as both creator and steward.

Recycling as Ritual and Resistance

In many indigenous and grassroots communities, the reuse of materials is not a trend but a tradition. The act of recycling carries spiritual and cultural dimensions, embodying respect for the Earth, resourcefulness, and resilience. Artists working within these frameworks often engage in what we might call material storytelling, where every object, no matter how small, retains its narrative power.

In the Eco Rasquachismo movement, a concept grounded in Chicanx aesthetics, artists embrace the «low» or the marginal to critique capitalism and environmental injustice. By using found objects, repurposed textiles, and urban detritus, they engage in a creative form of resistance. Their works are layered with humor, memory, and protest, turning the everyday into the extraordinary.

Recycled art becomes especially potent in the realm of installation, where space and scale intensify message and meaning.

Let’s consider Chris Jordan’s powerful piece «Midway: Message from the Gyre», which documents dead albatross chicks on the Pacific island of Midway, their stomachs filled with plastic debris. His photographs are haunting evidence of the silent horror of pollution. Although technically photography, the series serves as a visceral installation in the minds of its viewers, forcing an emotional reckoning with the impact of plastic waste on ecosystems.

Similarly, the global «Washed Ashore» project creates massive sculptures of marine life using ocean plastic collected from beaches. These works are not confined to galleries but are installed in public spaces like zoos and aquariums to spark dialogue about plastic pollution. The tactile, colorful nature of the installations appeals to viewers of all ages, reinforcing the connection between human habits and marine life.

Participatory Practices: From Community Waste to Collective Work

Photos: Bahia Shehab, Hadeer Mahmoud, Mahmoud Nasr, Markus Lange

One of the most transformative aspects of recycled art is its capacity to be participatory. By involving communities in the collection, preparation, and creation of artworks, artists blur the line between creator and audience. These projects often have therapeutic, educational, and activist dimensions, empowering participants to see their environments, and themselves, through new eyes.

In Egypt, artist and scholar Bahia Shehab created a large-scale pyramid constructed entirely from Cairo’s street trash with the help of local children and workers. Her work was not only about aesthetics but about visibility, making the often-overlooked reality of waste a central visual and political issue. Similarly, projects like Recycle Santa Fe Art Festival provide platforms for artists working with reclaimed materials, fostering community engagement, and supporting green economies through creative entrepreneurship.

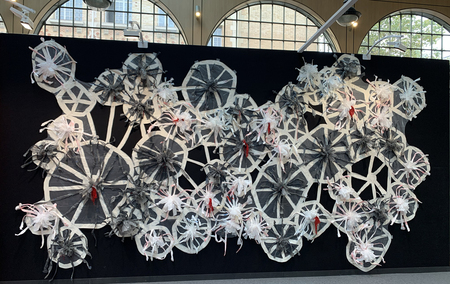

Invasive macroorganisms, Plastic bags, plastic sheet, latex paint. Nnenna Okore, 2022

Recycled materials do not arrive in the studio as blank slates, they come with histories, with marks of use, with scars and stories. The artist who works with these materials becomes a kind of archaeologist, uncovering narratives embedded in the objects themselves. This makes recycled art deeply layered, each piece not only comments on ecological issues but also on culture, economy, and time.

Artist Nnenna Okore, for instance, works with biodegradable materials like newspaper, jute, and old fabric to explore themes of decay, regeneration, and communal memory. Her sculptural installations mimic organic forms, fungi, roots, coral reefs, offering a metaphor for the interconnection of ecological and human life. Okore’s work, often inspired by the recycling culture in Nigerian communities, speaks to sustainable practices that have long existed outside Western capitalist systems.

Education Through Creation

Recycled art is a powerful pedagogical tool. When students, young people, or community members are invited to create art from waste, they experience first-hand the transformative power of creativity. The process cultivates environmental awareness not through lectures, but through touch, collaboration, and storytelling.

Many schools and museums now run workshops in recycled art. One notable example is the Children’s Forest Pavilion at the COP21 climate conference in Paris, where children from around the world submitted artworks made from local waste. The pavilion became a mosaic of youthful visions for the planet, a hopeful, collective voice built from the very materials threatening their future.

Such educational initiatives demonstrate that recycled art is not merely reactive but generative. It plants seeds of change in the minds of those who engage with it, shaping not just artworks, but new environmental stewards.

Kamilo, 2011 SCULPTURE

Artist: Aurora Robson Dimensions: Approx. 5' x 4' x 3' Materials: Plastic marine debris

There is a growing consciousness within the art world around the environmental footprint of artistic production itself. Traditional practices, such as the use of toxic paints, mined minerals, or synthetic polymers, can be harmful to both artists and ecosystems. Recycled materials offer a more ethical alternative, aligning the method of creation with the message being conveyed.

This is evident in the work of artist Aurora Robson, who intercepts plastic waste before it enters waterways and transforms it into mesmerizing sculptures that look like jellyfish or alien flora. Her art addresses plastic pollution, but equally important is how it is made: Robson’s entire practice is rooted in diverting waste from landfill and raising awareness through sustainable methods.

This ethic extends to architecture and design as well. Firms like Studio Swine have created furniture and installations using recycled aluminum, sea plastic, and human hair, challenging not only how we create, but how we consume.

Urban Interventions and Public Consciousness

When recycled materials are used in public art, their message gains visibility and immediacy. Unlike works confined to galleries, urban interventions speak to everyone: the commuter, the child, the passerby. These pieces often blend aesthetics with activism, functioning as both artwork and public service announcement.

The artist «Bourdallo II» hosted a series of «trash sculptures» made from street litter, strategically placed in high-traffic areas. The sculptures were not only visually engaging but embedded with QR codes linking to information about local recycling programs.

In this way, art became an interface between individual awareness and collective responsibility. Such urban eco-art reminds us that public spaces are not neutral, they are sites where values are negotiated, behaviors modeled, and change made visible.

Bordallo II Trash Sculptures, 2021

Waste as Witness: The Political Dimensions of Discarded Materials

Recycled art is not only environmental, it is political. Every item we throw away is an artifact of systems: of inequality, of global trade, of labor exploitation, of climate injustice.

When artists incorporate waste into their practice, they are often making a political statement, not just about the environment, but about who bears the brunt of environmental degradation and who has the power to change it.

Artist Manuel R. Miranda, for example, created large-scale installations out of discarded materials in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. His work, assembled from the storm’s aftermath, broken furniture, metal scraps, torn signs, was a form of mourning, but also a critique. It pointed to the colonial relationship between Puerto Rico and the mainland United States, highlighting how recovery efforts left behind both people and place.

Mary Mattingly, WetLand, 2014. Mixed media, dimensions variable.

Many contemporary artists working with recycled materials are also engaging with climate grief, the complex emotional response to ecological collapse, species extinction, and global warming. Art becomes not just a medium of activism, but one of processing sorrow, loss, and uncertainty.

Take the work of Mary Mattingly, whose floating installations made of salvaged goods and edible plants speak to a future of water-based living in flooded cities.

Her project «Swale», a floating food forest in New York City, blurs the line between installation and intervention. Built from recycled wood, containers, and waste material, it is both a poetic metaphor and a practical survival blueprint.

Recycling in Institutional Shifts and the Role of Galleries

As artists increasingly incorporate recycled materials, art institutions must also evolve. More galleries, museums, and art festivals are now embracing sustainability, not just as a theme, but as a practice. Some have adopted zero-waste policies for installations. Others host «green residencies, ” where artists are provided only with found or salvaged materials to work with.

The London Design Museum has hosted exhibits like „Waste Age“, spotlighting design, fashion, and art that addresses throwaway culture. Meanwhile, platforms like Art Works for Change continue to amplify the voices of eco-artists globally, curating exhibitions focused on climate change, social justice, and the power of creative activism.

These shifts within the institutional space are essential. They validate the work of recycled artists, bring eco-issues into public consciousness, and help reshape the art market itself.

Algae bioplastic sequins dress by Charlotte McCurdy and Phillip Lim

The Peak Waste section

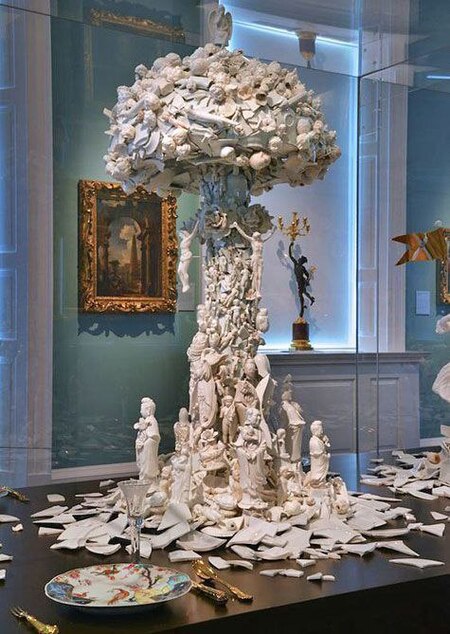

Blast Studio’s Tree Column is made from discarded coffee cups and mycelium Photography by Felix Speller

In Summary: A New Ethics of Creation

As we bring this chapter to a close, one truth resounds: the choice of material is never neutral. When artists choose recycled matter, they choose to tell a different story, a story of continuity, resilience, and reclamation. They take what was once broken, discarded, or invisible, and bring it into the light.

It’s critical to acknowledge that many artists in the Global South have long worked with recycled materials, all because of ecological trends, but due to economic necessity and cultural tradition. These practices reveal how recycled art can be both deeply local and globally relevant. They remind us that sustainability is not new it has always existed where necessity met creativity, long before it became fashionable in the art world.

This is the heart of Creativocacy, the belief that art is not a passive reflection of the world, but an active participant in its reimagination.