Coining Creativocacy: Creativity Meets Advocacy

Not all revolutions need words—some are painted, sculpted, and woven from the remnants of the past.

Creativocacy is more than a term; it is a movement, a manifesto, a battle cry for artists who refuse to create passively. This chapter explores how artists use their work as a form of resistance, storytelling, and policy-changing activism. From visual statements on climate change to guerrilla installations protesting overconsumption, this is where art ceases to be decoration and becomes disruption. Through stunning case studies and provocative examples, this chapter answers: how does creativity become a weapon, and what happens when advocacy wields the brush?

Creativocacy, is the deliberate use of artistic expression to shift public narratives, engage communities, and drive social change. It is not passive or accidental, it is a public, intentional, and goal-oriented act that uses creative forms to challenge the status quo and inspire movement toward a better future.

While advocacy can sometimes support existing systems, creative advocacy typically emerges where dominant narratives are limiting awareness, connection, or action. It aims to open new ways of seeing problems and possibilities, helping communities imagine and build more just, sustainable futures.

JR’s Inside out project

Let’s break down the key elements:

- Creativocacy is public Creative advocacy lives in the public sphere. Unlike private conversations or internal thoughts, it takes the form of visible, shared action, like a mural, a performance, or a social media campaign, designed to be seen, felt, and responded to by others. Let’s consider Project: JR’s Inside Out Project French artist JR invites communities worldwide to share their portraits and paste them in large-scale public spaces, walls, streets, rooftops, transforming cities into galleries. This participatory global project uses public art to address themes like identity, diversity, and injustice, making private stories visible in public view.

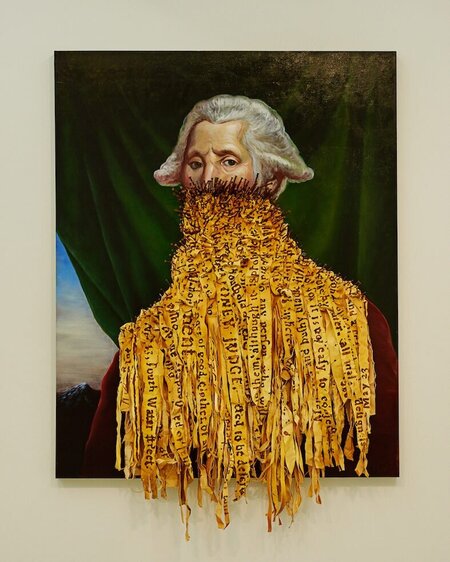

Titus Kaphar, Absconded from the Household of the President of the United States (2016)

- Creativocacy is intentional This is not about accidental inspiration. Creative advocacy is purpose-driven. It is created with the clear goal of influencing perception, sparking dialogue, or shifting behavior.

An example is the Project by Titus Kaphar.

Titus Kaphar creates work that intentionally reinterprets historical paintings by altering them, cutting, whitewashing, or layering to highlight the absence or erasure of Black bodies and voices in art history. Each piece is a calculated act to reveal what traditional narratives overlook and push forward conversations around racial justice.

Ghost Forest, 2021 Madison Square Park, New York, NY Commissioned by Madison Square park Conservancy 49 Atlantic Cedar trees (36 — 46 feet)

Photography: Andy Romer, courtesy MSPC Additional Photography: Maya Lin Studio

- Creative Advocacy Employs Artistic Practice

What sets creative advocacy apart is its reliance on art and design from street art to music, film, fashion, theater, and beyond. It brings in the power of emotion, aesthetics, and symbolism to amplify its message and deepen its impact.

An example is The Ghost Forest by Maya Lin This installation featured a group of dying Atlantic white cedar trees placed in Manhattan’s Madison Square Park. Through a stark and poetic visual language, Lin used sculptural practice to communicate the ecological loss caused by climate change and deforestation, prompting viewers to consider environmental fragility through an artistic lens.

- Creative Advocacy mostly Goal specific, Engages and Builds Community

Every act of creative advocacy is aimed at a community or audience, whether tightly defined or broad and diffuse. It doesn’t just speak at people, it speaks with them, inviting participation, reflection, and sometimes co-creation.

The Laundry Project by Lava MaeX was a mobile art-and-service project transformed laundromats into pop-up community spaces offering free laundry services, hygiene supplies, and live music or poetry for unhoused individuals. While not gallery-based, the project merges creativity with care, using design and performance to foster dignity, dialogue, and connection among underserved populations.

What Happens When Artists Refuse to be Silent?

This chapter is about the fire that burns within every artist-activist, the unshakable belief that creativity can be more than expression, it can be resistance.

Throughout history, art has been wielded as a weapon, its sharp edges cutting through oppression, injustice, and environmental destruction. Yet, traditional advocacy has often relied on words, petitions, speeches, policies. Creativocacy challenges this norm, proving that sometimes, a single sculpture can carry more weight than a thousand manifestos. A mural can amplify the voices of an entire community. A performance piece can shake the world awake.

Consider the haunting works of Ai Weiwei, who uses art as a medium for dissent and human rights advocacy, especially regarding freedom of expression, government transparency. His voice became internationally prominent after he openly criticized the Chinese government. In one of his works, he transformed piles of life vests discarded by refugees into an installation that forces viewers to confront the human cost of displacement.

Ai Weiwei — Soleil Levant, 2017, life jackets in front of windows of facade, Kunsthal Charlottenborg, 2017, photo: Anders Sune Berg

Ai Weiwei’s work reminds us that art can be an act of resistance. His fearless confrontation of authority, ability to merge traditional Chinese aesthetics with global issues, and his commitment to exposing injustice has earned him a place not just in museums but in history books. In an age of surveillance and misinformation, Ai stands as a testament to the artist’s role as a truth-teller.

In the realm of creativocacy, where creativity becomes a vehicle for advocacy, few artists wield visual language as sharply and impactfully as Banksy. His guerrilla art composed mostly of stenciled street pieces may appear deceptively simple at first glance, but they are, in fact, intricately loaded with meaning, urgency, and resistance. Each work is a visual disruption, breaking the monotony of public spaces and challenging the passerby to pause, reflect, and confront the uncomfortable truths hidden in plain sight.

Banksy doesn’t seek approval, galleries, or permission. His art appears unannounced in the most unexpected places: crumbling walls, urban alleys, or even war-torn zones. And yet, these transient, often illegal installations command global attention. They are acts of creative defiance that bypass institutional filters and speak directly to the public.

Girl with heart balloon (2006); Flying Ballon Girl on the West Bank wall at Kalandia (2005); No Future in Southampton (2010) There is Always Hope, version in South Bank (2002) Artist: Banksy

Take for example his piece «Girl with a Balloon», seemingly innocent, a child reaching for a heart-shaped balloon and yet, it resonates universally as a symbol of lost innocence, fleeting hope, and human fragility. When it self-destructed moments after being auctioned at Sotheby’s, it wasn’t just a prank. It was a powerful commentary on the commodification of art, a statement that art made to challenge systems should not be absorbed and neutralized by those very systems.

His mural «There Is Always Hope», painted near London’s South Bank, or «Season’s Greetings», which reveals a child joyfully catching snowflakes on one side, and a dumpster fire fueling the flakes on the other, show how Banksy manipulates duality to expose environmental hypocrisy and systemic failures. These works don’t scream; they whisper and in doing so, they amplify.

Agnes Denes, «Wheat Field-Confrontation», New York, 1982 © agnesdenesstudio.com / Agnes Denes

Eco-artists like Agnes Denes have long been pioneers in the realm of creativocacy using creative expression not just to make art, but to advocate for a profound rethinking of our relationship with nature, economics, and the future of our planet. In one of the most iconic acts of environmental art and visual protest, Denes planted a two-acre field of golden wheat in the middle of Battery Park Landfill in Manhattan in 1982, a bold gesture that became known as «Wheatfield: A Confrontation.»

This was not just a poetic intervention; it was a calculated act of defiance. At a time when Wall Street’s towers loomed over the city as monuments to wealth and financial power, Denes dared to insert agriculture, the most fundamental human act of survival, into the heart of a metropolis obsessed with profit and progress. The visual contradiction was staggering: a field of golden wheat swaying gently in the shadow of the World Trade Center, surrounded by the machinery of urban development.

Through this work, Denes posed a quietly radical question: what do we truly value? Is it the relentless pursuit of capital, skyscrapers, and stock markets or the living earth that feeds us, sustains us, and connects us to something older and more essential than any economic system?

By cultivating life where there was only landfill, she transformed waste into nourishment literally and symbolically. It was a temporal sculpture and a living manifesto, exposing the fragility of our environmental systems while urging viewers to reconsider land not just as real estate, but as a sacred, life-giving force.

Denes’ work goes beyond art as commentary; it becomes art as ecological philosophy, as land stewardship, as activism rooted in aesthetics. Wheatfield was harvested, the grain shared, and the work lives on in photographs and memory but its message remains urgent: we cannot separate ecological survival from cultural values. Her field was both a literal and metaphorical confrontation between nature and capitalism, beauty and utility, permanence and transience.

Creativocacy demands this confrontation. It insists that art must provoke, must disturb, must move people from indifference to action.

Vik Muniz, Pictures of Garbage

The modern world drowns in waste, plastic that chokes the oceans, landfills swelling with forgotten consumer goods, electronic waste leaking toxins into our soil. But in the hands of the eco-artist, these discarded remnants become more than refuse. They become statements.

What does it mean to sculpt an entire exhibit from ocean plastic? To craft jewelry from e-waste? To weave textiles from old fishing nets? These works are not just visually striking; they are confrontational artifacts that refuse to let us turn away from the consequences of our consumption.

In Brazil, artist Vik Muniz collaborated with landfill workers to create portraits of themselves using the very materials they scavenged daily. The result was a collection of powerful self-representations that not only honored the dignity of these workers but also exposed the stark realities of global waste management.

Vik Muniz, Wasteland

The Social Impact: As Muniz works with the catadores, their lives begin to change. The process of making art gives them hope and empowers them, leading some of them to shift their perspectives on their work and their potential. The film portrays how art can be a tool for social change, helping to raise awareness of issues like poverty and environmental degradation.

The Artworks: The final artworks, which are based on the catadores' portraits, are displayed in an exhibition, and the documentary captures the emotional response of both the artists (the catadores) and the viewers. Muniz’s approach not only elevates the dignity of the workers but also sheds light on the realities of life in the landfill.

Themes of the Film: Wasteland touches on themes of social justice, environmentalism, and the transformative power of art. It shows how something as simple as trash can be repurposed into art that celebrates human resilience and creativity, while also making a powerful statement about waste, both material and social.

From Art to Policy: When Creativity Moves Beyond Expression

Similarly, Dutch artist Daan Roosegaarde designed the Smog Free Tower, a public air purifier that converts pollution into jewelry. This project transcended art, merging into environmental engineering, proving that advocacy is most powerful when paired with innovation.

Turning Pollution into Jewelry: One of the most unique aspects of the Smog Free Tower is that it doesn’t just purify the air; it also turns the captured pollution into something useful and creative. Roosegaarde has developed a method to extract the collected smog and turn it into small, stylish pieces of jewelry, such as rings and cufflinks. This transformation symbolizes the idea that even pollution, a negative byproduct of modern life, can be repurposed and reimagined as something beautiful and valuable.

Environmental Awareness and Innovation: Roosegaarde’s Smog Free Tower is not only a functional tool for cleaning the air but also an artistic statement about environmental awareness and innovation. By turning smog into jewelry, Roosegaarde highlights the potential for creative, sustainable solutions to environmental problems.

Smog Vacuum in The Netherlands Turns Carbon Waste into Jewelry Courtesy of Studio Roosegaarde

As we conclude this chapter, Creativocacy is not just about visibility, it is about impact. While some works serve as wake-up calls, others evolve into tangible policy changes.

The world is at a tipping point. Climate change accelerates, inequalities deepen, and the lines between artistic creativity and advocacy blur further. The next generation of Creativocates will not simply create, they will intervene. They will redefine what it means to be an artist in the 21st century.

We are entering an era where art will not merely be displayed, it will be felt, lived, and enacted. Where sculptures will filter air, paintings will generate electricity, and installations will restore ecosystems. Where the lines between artist, scientist, activist, and innovator dissolve, creating a new breed of creative revolutionaries. The question is no longer whether art can change the world. It already is.

The question is, will we listen? Will we act? This is the age of Creativocacy.