The Material Revolution: A Paradigm Shift

Art is no longer what we create—it’s what we save, what we repurpose, and what we refuse to throw away.

There was a time when an artist’s worth was measured by the quality of their materials; marble, gold leaf, oil paints. Now, artists find richness in the abandoned, elegance in the excess, and innovation in the overlooked. This chapter explores how a global shift in material consciousness is redefining art itself. It asks: what happens when art is no longer just a product but a solution? When art materials are not extracted but salvaged? When what we discard is no longer lost, but found, and transformed into something that demands attention?

Across art history, visionary artists have reclaimed everyday junk and cast-offs, from scrap metal to plastic trash, and transformed them into powerful artworks. This chapter highlights landmark pieces that repurpose and elevate overlooked materials, introduces key artists known for sustainable and unconventional media, and points you to museum collections and galleries where you can explore these works.

Though recycling is often thought of as a modern phenomenon, the reuse of materials in art and craft dates back thousands of years: Ancient Civilizations: In many ancient cultures (Egyptian, Roman, Chinese, African), materials like metal, pottery shards, or broken statuary were repurposed in functional or decorative objects. Mosaics often included fragments of older ceramics or glass. Medieval Europe: Religious relics and shrines were often constructed using remnants of older churches, gold fragments, and broken statuary. Indigenous Traditions: In many Indigenous cultures worldwide, sustainability and circular use of materials have long been core values. Tools, textiles, and adornments were made from natural remnants, bones, shells, or broken tools passed through generations. While not called «recycled art» at the time, these traditions laid the groundwork for modern repurposing aesthetics.

Pioneering Artworks of Reuse and Transformation

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917, replica, 1964, via Tate

Dada Movement (1916–1924)

The formal embrace of found and repurposed objects as fine art began with Dadaists, reacting to the horrors of WWI and questioning traditional art values.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain (1917). Originally an upside-down porcelain urinal signed «R. Mutt 1917», Fountain shocked the art world by turning a piece of plumbing into art. Duchamp’s infamous readymade was a crass, ordinary object elevated to gallery status, a satirical jab at traditional art and arguably the first conceptual artwork

By choosing a mass-produced urinal and simply declaring it art, Duchamp upended material values and proved that creativity can reside in the act of selection as much as in craftsmanship. Fountain remains «one of the most iconic artworks in the history of modern art and the use of everyday found or unconventional objects in arts.”

Duchamp was one of the first artists to introduce manufactured objects into the gallery space, which he referred to as «Readymades.» His Fountain, a mass-produced urinal, was a provocative example of this approach, challenging conventional notions of what could be considered art. It was shocking not only for its form but for its rejection of traditional ideals of beauty and craftsmanship. Duchamp aimed to subvert the very idea of «good taste,» asserting that anything could be art if the artist designated it as such.

Duchamp’s challenge to the art world went beyond the physicality of the object; it was a radical statement about the value of ideas over objects. His philosophy would lay the foundation for much of Conceptual Art. In the context of Fountain, this was especially revolutionary because it questioned ideas of originality and authenticity, which had been deeply ingrained in the art world.

Duchamp’s Fountain Challenged Traditional Ideas of Originality, pushed the Limits of Freedom of Expression, and was a key milestone in The Material Revolution, reshaping art’s connection to everyday recyclable materials.

1920s–1960s: Surrealism and Merz, Junk Art and Neo-Dada

Pablo Picasso, 1942, Tête de taureau (Bull’s Head), bicycle seat and handlebars, 33,5×43,5×19 cm, Musée Picasso, Paris

Pablo Picasso, Bull’s Head (1942). In this witty assemblage, Picasso fused an old bicycle seat and handlebars to create the unmistakable form of a bull’s head. It’s a simple yet «astonishingly complete» metamorphosis of scrap into art Picasso found the rusty bike parts in a heap and instantly «knew what to do», he welded them together before he had a chance to second-guess.

Notably, he left the original objects fully visible: Bull’s Head «makes no attempt to play down the real-world identity of the constituent parts”.

This transparency invites the viewer to marvel at imagination’s alchemy, how a throwaway object can become art with a mere shift in perspective. Today the sculpture is in the permanent collection of the Musée Picasso in Paris, celebrated as a classic example of found-object art.

Louise Nevelson. Sky Cathedral. 1958

Let’s consider Louise Nevelson, Sky Cathedral (1958). A towering wall assemblage of discarded wooden fragments, Sky Cathedral exemplifies Nevelson’s ability to turn urban detritus into spiritual art. She salvaged scrap wood from old buildings, furniture legs, spindles, moldings, and fitted them into stacked box-like «cubbies, ” all unified by a coat of flat black paint.

The result is an 11-foot tall monochrome relief pulsing with shadow and depth. Nevelson described herself as „the architect of shadows, ” and here the once-forlorn wood pieces are reborn as a majestic „cathedral“ of forms.

By erasing the wood’s past lives under black paint, Nevelson „obliterated the past histories of the pieces“ to give them a new, unified identity. This iconic work (now at MoMA, NY) shows how cast-off materials can be orchestrated into monumental expressions of memory and spirituality.

Monogram, Robert Rauschenberg Abstract Expressionist Oil on Canvas, Paper and Wood Painting, 1955 to 1959. The image is © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Robert Rauschenberg, Monogram (1955–59). Rauschenberg pushed art beyond painting with his «Combines», which merged canvases and found objects. Monogram is his most famous Combine: a taxidermy Angora goat encircled by a automobile tire, standing on a collage-painting base.

The goat, reportedly found in a secondhand shop for $15, wears the tire like a hulking necklace, forming an almost absurd hybrid creature. Critics describe Monogram as Rauschenberg’s masterpiece, one that blurs sculpture and painting using society’s cast-offs. Scattered on the base are urban flotsam (a shoe heel, paint tubes, a tennis ball), creating a textured «pasture of detritus» around the goat.

By integrating trash and a once-living animal into art, Rauschenberg dramatized the beauty and chaos of postwar consumer culture. Monogram (collection of Moderna Museet, Stockholm) remains a bold statement on recycled materials in art crafted from the leftovers of life.

To be a true ecologist today, one must re-establish the aesthetics of beauty within the realm of human trash and material waste. –Slavoj Žižek

1960s–1970s: Arte Povera and Earth Movements

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags (1967, 74)

In the light of this, the artwork by Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venus of the Rags (1967) speaks volumes. A cornerstone of Italy’s Arte Povera movement, this installation pairs a classical statue of Venus with a towering pile of discarded rags. The elegant marble Venus stands facing a mound of old clothes, as if contemplating our culture’s waste. Venus of the Rags has been called «an emblem of throw-away culture, ” forcing a confrontation between ideal beauty and trash.

Pistoletto literally inserted garbage into high art, „urging us to consider the aesthetic of decay and how that can inform a new & timely re-consideration”. The piece’s jarring contrast delivers a sharp critique: even the goddess of beauty cannot ignore modern overconsumption. By using rags from his studio, the very cloths that wiped his mirrors, Pistoletto gave waste material a second life and challenged viewers to find beauty and meaning in society’s cast-offs.

1980s–1990s: Urban Decay, Assemblage & Cultural Critique

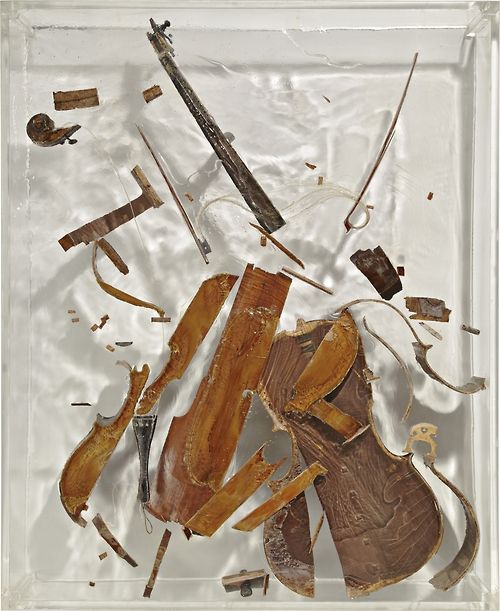

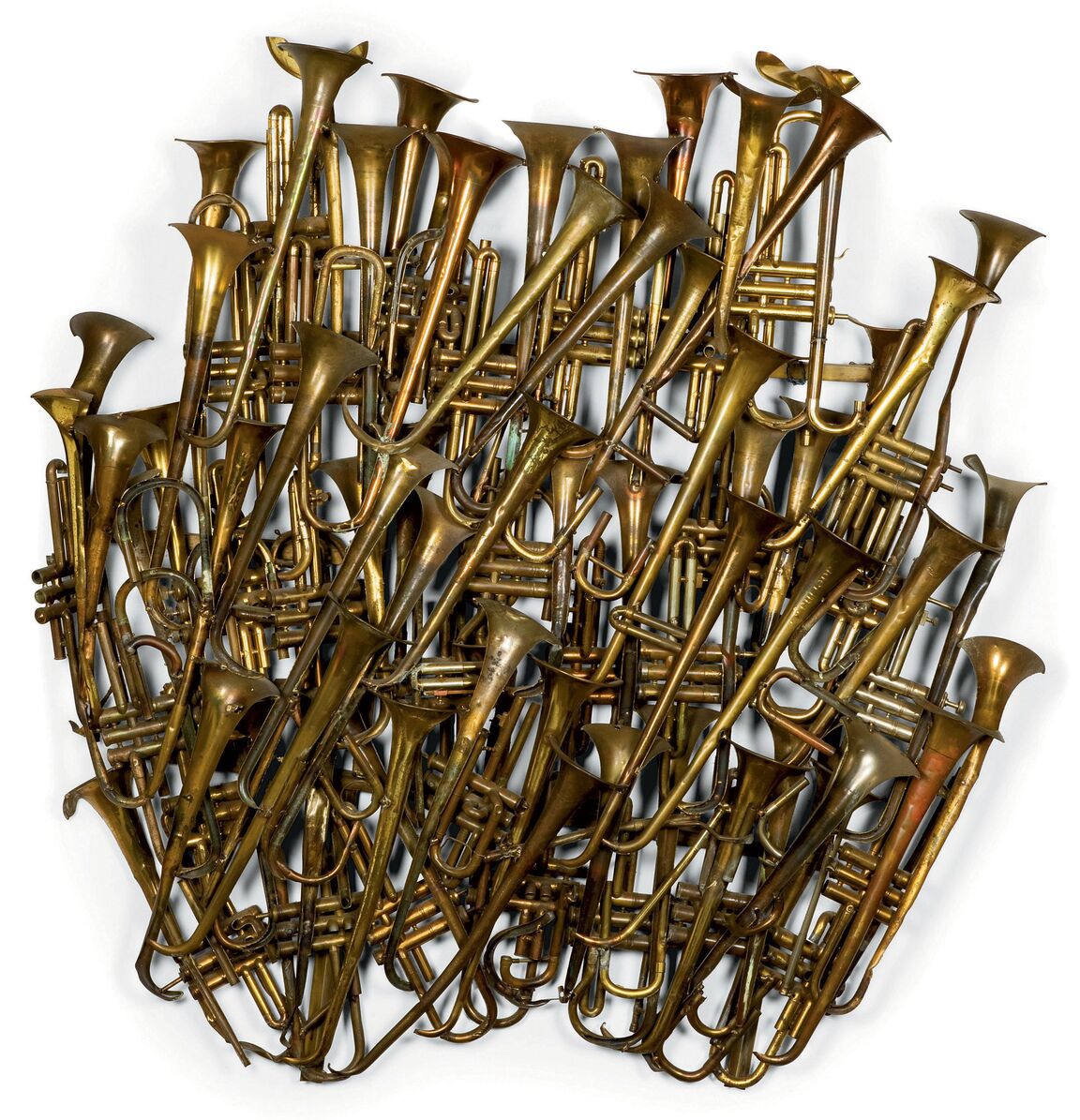

ARMAN (1928-2005) — Untitled, 1972 Peinture, Sculpture Gillespie’s Syndrom 1980s, Pyraviole II Christie’s Sculpture contemporaine, Art plastiq Accumulation of Violins (1928-2005) Forks and Spoon

Arman (1928–2005), A French-born Nouveau Réaliste known for Accumulations of found objects (like hundreds of gas masks or violin parts) and sealed «Poubelle» boxes filled with actual garbage. By gathering multiples of discarded items, Arman’s work commented on consumer excess and waste.

Arman’s use of recycled materials can also be understood within the context of creativocacy, an approach that blends art, advocacy, and social consciousness. His work didn’t just highlight the physical materials that were discarded, but also questioned the broader implications of a throwaway culture, calling attention to the unsustainable practices that contribute to environmental degradation. Arman’s art is an early example of how recycled materials in art can serve as both a creative tool and a powerful form of activism.

Late 20th Century to Early 21st Century: Sustainability and Global Dialogue

Sustainable Art Movement (1990s–2000s)

As environmental awareness grew, artists began creating explicitly eco-conscious works, and the Global Perspectives increased. Artists from the Global South began using recycled materials to speak on colonialism, poverty, and environmental injustice.

Tim Noble & Sue Webster (b. 1966/1967) are a British artist duo renowned for their innovative and thought-provoking «shadow sculptures.» Their works are created by meticulously arranging piles of discarded items, ranging from taxidermy animals and broken tools to household waste, into complex heaps. When these piles are lit in specific ways, they cast shadow portraits on the wall, revealing intricately detailed images that transform ordinary trash into profound visual statements. Their art, particularly their shadow sculptures, challenges the perception of waste and highlights the potential for transformation and creativity in the most unlikely of materials.

One of their most famous works, Dirty White Trash (With Gulls) (1998), features six months’ worth of their personal garbage, which has been carefully arranged to form a self-portrait in shadow. This piece is a witty, yet poignant commentary on the concept of recycling, illustrating how even the most mundane and discarded materials can be repurposed to create something meaningful and personal. The fact that their own waste forms a reflection of themselves, literally casting their self-portrait in shadow.

The Individual, 2012, Wild Mood Swings, 2009-2010 Wasted Youth, 2000 Dirty White Trash (With Gulls), 1998 Miss Understood & Mr. Meanor, 1997

Tim Noble and Sue Webster

Key Characteristics of Recycled Art Movements

Recontextualization: Elevating ordinary or discarded objects into meaningful art. Anti-elitism: Challenging traditional materials and values of the art world. Sustainability: Responding to global ecological crises and overproduction. Memory & Identity: Using material culture and found objects to explore race, gender, and history. Community Engagement: Participatory projects involving local waste and people.

Conclusion: Toward a New Material Mindset

As we conclude this chapter, we discover that by the early 21st century, recycled materials in visual arts had evolved from provocative gestures to powerful tools for storytelling, activism, and sustainability. Artists were no longer just reclaiming materials, they were reclaiming meaning, confronting society’s values, and transforming the very definition of artistic value. This journey, spanning from ancient reuse to Duchamp’s urinal, from Arte Povera’s rags to Muniz’s garbage portraits, shows a rich and global history where materials themselves become part of the message. As environmental concerns intensify, this lineage continues to inspire artists in the 21st century to create with consciousness, care, and purpose.